Humanity and the Malthusian Trap

In this post from the book NET-ZERO:

What was the climate like for early humans? A brief history of Planet Earth and civilisation.

Who was Thomas Robert Malthus? Population, pestilence, and the planet’s resources.

How fast is the global population increasing? The power of exponential growth - interest, viruses, and procreation.

A Brief History of Earth, Humans, and Civilisation

The Universe started with the Big Bang, some 14 billion years ago. Another 9.5 billion years passed before our solar system settled and planet Earth formed from the gravitational pull of hot swirling gas and dust.

Earth cooled, lava turned to rock, water condensed into oceans, and the first single celled organisms appeared four billion years ago. These simple lifeforms eventually chanced upon a route to harness and store energy from the sun; photosynthesis released huge quantities of waste oxygen.

Earth’s systems were overwhelmed, and its atmosphere irreversibly changed.

This Great Oxidation event, two billion years ago, led to the evolution of increasingly complex life. Early plants formed nearly one billion years before the present day. The colonisation of land, with the expansion of dense forests, dates back 500 million years.

Dinosaurs were roaming the planet 230 million years ago, swiftly followed by the first mammals on Earth, shrew-like creatures which inhabited a planet 10-15 ⁰C warmer, with sea levels over 200 metres higher, great forests stretching to the poles, and crocodiles swimming in the Arctic.

Early humans didn’t evolve until the temperature of Planet Earth had cooled by 10-15⁰C. We first mastered walking on two legs, allowing us to cover vast distances. Then Homo habilus “The Handy Man” developed stone tools around 3 million years ago. Our earliest close ancestors, Homo erectus, are the longest lived of all human species and first appeared nearly two million years ago, surviving multiple ice ages until extinction 1.7 million years later. Homo erectus learnt to hunt, to fashion stone tools, and to cook food.

Modern human existence is a mere tick on the geological clock

Modern humans or Homo sapiens first evolved just 300,000 years ago: if the existence of planet Earth were condensed into the 24 hours of one day, we would appear just 6 seconds before midnight.

Nonetheless, we have made good use of our time with early Homo sapiens developing language, art, and social co-operation. These attributes no doubt helped our nomadic hunter gatherer ancestors to survive another series of ice ages where average temperatures dropped 4-8⁰C below today and vast ice sheets, thousands of metres thick, extended across Europe, North America, and one third of all the land on Earth.

The Egyptians formed the first human settlements 13,000 years ago but volatile temperatures and unpredictable weather forced their return to nomadic life.

Human civilisation began in earnest 12,000 years ago (0.2 seconds before midnight) when the temperature of the planet settled into a stable range very similar to today.

We became the dominant species on planet Earth and asserted our authority over the natural world by clearing forests for crops, rearing animals for food, and re-purposing the earth’s natural resources. Humans developed agriculture, writing systems, philosophy, religious order, cities, empires, and global trade.

We're caught in a trap

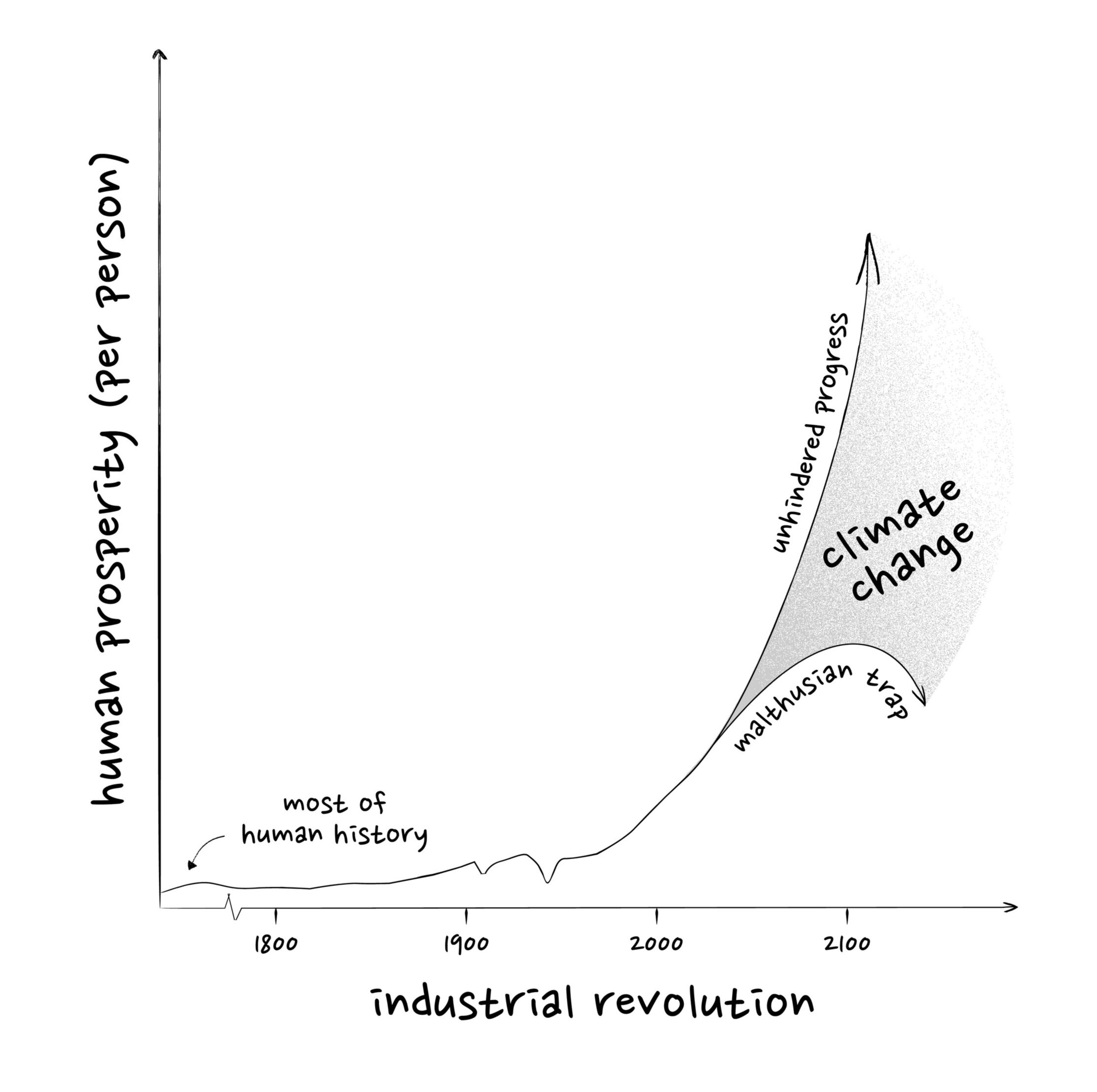

Yet despite the achievements of humanity, for most of human history the majority of humans have experienced very little improvement in quality of life. Records of GDP or income per person dating back 2,000 years show the average human earnt the equivalent of less than $1,000 per year (in today’s money) through most of this period.

The total sum of global GDP may have increased or decreased with population and the distribution of wealth certainly changed depending on the whims of the ruling elite, but productivity was stuck at $1,000.

So although the experience of life would have been very different for your average human living in 16th century Shakespearean England compared to Cleopatra’s Egyptian empire in 50 BC, the prevalence of disease, war, and hunger were pretty similar.

Humans have a potential life span of 70 years but for most of human history life expectancy was pegged at 20 to 40 years due to the prevalence of child mortality, disease, malnutrition, and violence.

Humanity was stuck in the Malthusian Trap.

In 1798, Thomas Robert Malthus, an English cleric and economist, published his book ‘An Essay on the Principle of Population’ asserting how any increase in resources, such as an abundance of food, will inevitably lead to population increase. Improved living standards don’t last long because the rising population soon begins to exhaust the extra nourishment, so quality of life deteriorates and famine, and disease once again rise so that human prosperity is once again reset.

Malthus considered increases in available resources to be linear and unchecked population growth to be exponential – as the maths seemed incompatible, so famine, disease, and war would inevitably hold back the human species.

The Power of Exponential Growth

Let’s pause for a moment and dig into the difference between linear and exponential growth.

Linear increase is the more intuitive notion, where one variable will change by a given amount when compared with the change in a second variable. For example, if you invest £100 and earn 10% interest on this original deposit each year then, after ten years, you have £200 in your account. You make a linear increase of £10 interest for every one year of time.

Exponential growth, on the other hand, is where the rate of change in one variable depends on the magnitude of the other variable. An example in finance is called compound growth, where the interest accumulated in your account earns more interest. Imagine you deposit your £100 at 10% annual compound interest, then after the first year you have £110, but in the second year the extra £10 also earns interest: you end up with £121 by the end of year two. If you let your investment compound at 10% per year for 10 years you end up with £259 in savings, which is significantly more than in our linear interest example.

“The most powerful force in the Universe is compound interest.” Albert Einstein

There are many aspects of modern life where we experience exponential growth. Economists expect GDP to grow at 1-3% per year compound; we have learnt the hard way that viruses spread exponentially; and as Thomas Malthus pointed out, the human population itself has followed an exponential path through history.

At the start of the agricultural revolution there were less than five million humans on the planet. It took two thousand years to reach 10 million people, a further 1,500 years to reach 20 million, and the population kept on doubling every 1-2 thousand years: a compound growth rate of 0.05% per year. By the year 1,500 AD, half a billion humans inhabited planet Earth and exponential change kicked up a gear: in just 350 years the population doubled again to just over one billion people. Another 75 years went by and we hit two billion people with the compound growth rate running at over 1% per year.

By 1974, the population hit four billion and is now nearly eight billion people today. We are currently adding, every year, around eight million people or the equivalent of one extra Greater London to the global population.

As Malthus put it:

“The power of population is so superior to the power of the Earth to produce subsistence for man that premature death must in some shape or other visit the human race. The vices of mankind are active and able ministers of depopulation. They are the precursors in the great army of destruction, and often finish the dreadful work themselves. But should they fail in this war of extermination, sickly seasons, epidemics, pestilence, and plague advance in terrific array, and sweep off their thousands and tens of thousands. Should success be still incomplete, gigantic inevitable famine stalks in the rear, and with one mighty blow levels the population with the food of the World.” An Essay on the Principle of Population, 1798.

So was Malthus correct - are we doomed to return to the same quality of life as all of human history before? Could climate change prove humanities undoing? How did we break free from the Malthusian Trap? And how long can we hold on to our liberty?

For more resources on a history of human progress please see ‘The Human Planet’, ‘Contours of the World Economy’ and ‘Our World in Data’ in the bookshelf.