Attribution, Participation, and Collective Action

In this post from the book NET-ZERO:

What is the difference between weather and climate? Understanding and attributing the impacts of climate change to support collective action.

Why is collaboration important for solving climate change? Working together for a least cost solution and the hurdles-to-action of freeriding and self-interest.

How can the world unite on tackling climate change? The iterative prisoner’s dilemma, overcoming self-interest, and the slow progress on global climate negotiations.

Attribution & Understanding

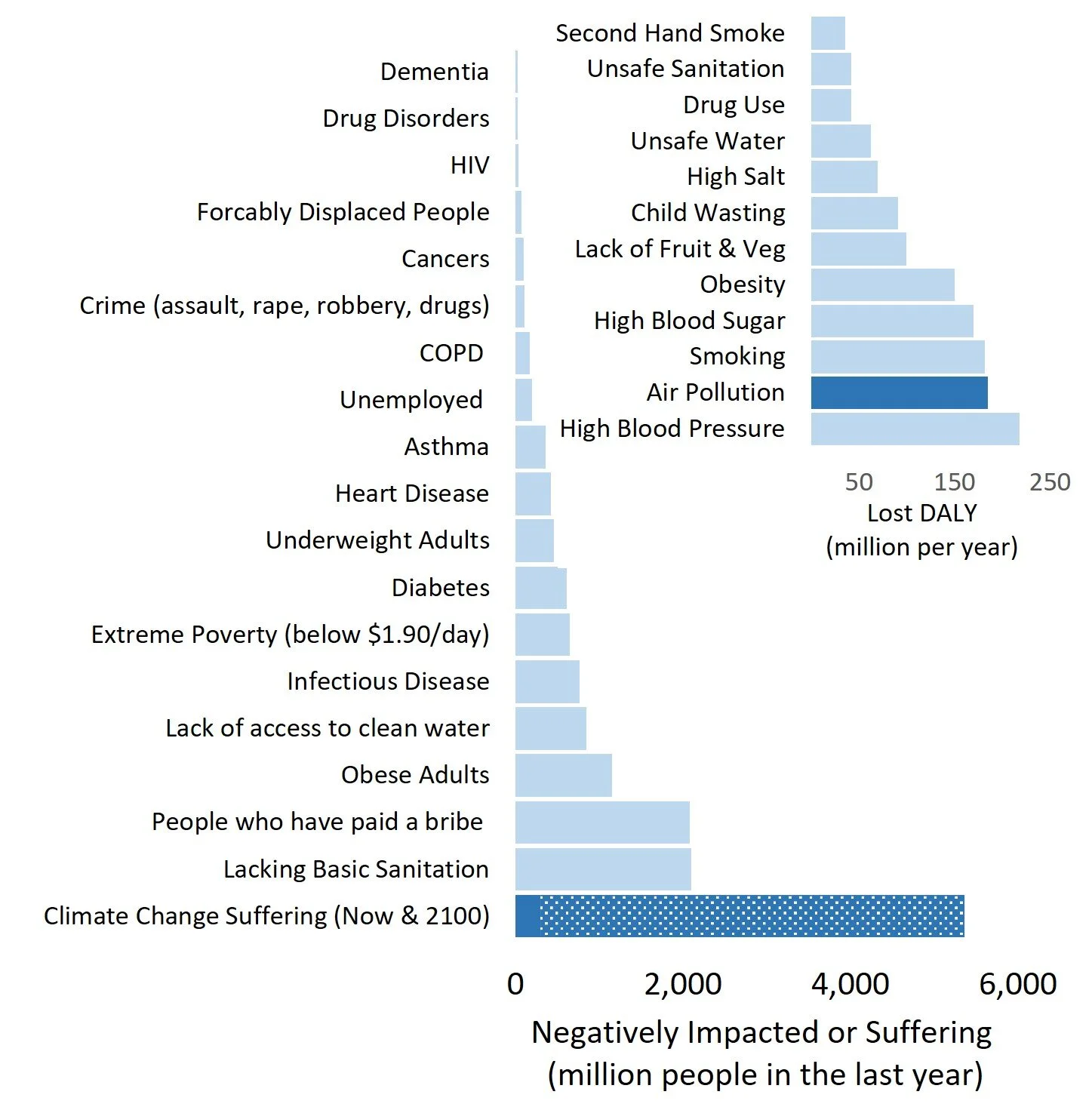

Climate change and air pollution are already a top-three global problem with the potential to take the undesirable number one spot due to a combination of death, suffering, and economic loss.

Air pollution, hidden hunger, productivity losses, and natural catastrophes are already taking their toll on the world. If left unchecked, climate change will likely spill over into nearly every other socio-economic and environmental problem.

But attribution of these impacts is tough and can act as a hurdle to change.

Humans have evolved to pass on information through story telling: stories grounded in specific events we have seen, heard, or felt at a specific time and specific place. We store these events in our long-term memory, aggregate, and share the stories as we express our views or form our opinions.

Climate change, in much the same way, is the statistical variation in weather patterns which when aggregated create a trend. Weather encompasses short term changes to the atmosphere which can culminate in a natural disaster. Climate is the trend of weather events over longer periods of time. As British Geographer and Oxford Professor Andrew John Herbertson put it, “Climate is what you expect, weather is what you get”.

But individuals cannot gauge one degree average temperature change over multiple decades and humans are predominantly sight animals - seeing is believing - but CO2 and temperature are invisible, and the weather seems unpredictable. How do we experience climate change?

Scientists can calculate the increased likelihood of flooding, fire, or drought due to a warmer atmosphere, but cannot definitively assign a single weather event to global warming because the system is too complex, with much internal variability. Climate change is measured in decades and over the entire planet and is neither specific in time nor specific in space.

Individuals, governments, and corporates operate on shorter timescales and in smaller regions. From next month’s pay cheque, to five-year election cycles, and 10-year investment plans, we are not used to thinking and planning for long-term change.

When farmers in Illinois were asked to recall growing conditions over the last seven seasons, their memories were more influenced by their pre-existing beliefs than the actual weather: those that believed in global warming thought it got drier, those that didn’t remembered no change.

The impact of Global Warming seems distant. The risk is that we reset expectations each year for more extreme weather, drought, and fire, and therefore normalise the increasing threat. We win the ongoing fight against our future selves and future generations but at what cost?

Broad-based understanding of the evidence and actions of climate change is needed to give individuals, corporates, and governments the confidence to enact behavioural change.

Participation and Collective Action

Net-zero is slightly more expensive today but becomes significantly cheaper once scaled. A harmonised, collaborative transition to net-zero over the next twenty years would create a beneficial socio-economic and environmental outcome for all.

But if the world doesn’t transition at the same rate this creates a potential hurdle to change. Those who move first bear more of the experience costs and install a greater share of zero carbon technology at higher prices. A first mover disadvantage. Furthermore, should a portion of the world refuse to decarbonise, then costs increase for everyone else because the optimal mix of technologies cannot be deployed.

Europe has been an early adopter of renewables technology and played a large role in driving wind and solar costs down the early part of the experience curve. In 2004, Germany was the first country in the world to implement a renewables generation subsidy which paid €46c per kWh of solar electricity (four times the global retail price). The levels of installations were uncapped and the generous pay-out created the beginnings of the solar boom.

However, those subsidies have also left Germans paying €6c per kWh, or 20% of their electricity bill, to cover past renewables incentives. Compare that to the US, the richest country in the world with one of the highest per capita emissions, and the take-up of net-zero technologies has lagged by at least five years: this is learning by watching or freeriding.

Game theory, which is the science of strategic decision making, is often used to try to understand the likely outcome of climate negotiations and the extent of global participation. Individual actions by countries across the world are often compared to the “prisoner’s dilemma”, a paradox where two bank robbers are held as suspects in police custody but, with no evidence, both are offered the option to testify against the other for a reduced sentence. The best outcome is for both suspects to co-operate with each other, keep quiet and go free, but neither robber is sure whether the other will talk or not. Game theory suggests both will pursue their own self-interest, opt for a reduced sentence, and each of the suspects will do time: a less than optimal outcome.

Climate negotiations are often likened to the “prisoner’s dilemma”: why would individual countries take action to reduce emissions when they cannot be sure other countries will act? Self-interest surely suggests taking no action and waiting for others to pay the higher upfront technology cost whilst enjoying the free-rider benefit. Another example of the tragedy of the commons.

Overcoming Hurdles to Change

The transition to a cheaper and better net-zero system is inevitable, but change is happening too slowly. Attribution and Participation are just two examples in a long list of other hurdles (apathy, inequality, market failures, tragedy of the commons, political wrangling, and deliberate sabotage) which must be overcome if we are to create change for the better, and drive a rapid transition to net-zero.

Attributing, understanding, and acknowledging not only the impacts of climate change, but also the benefits of net-zero creates cultural change and supports collective action. It is up to all individuals, corporates, and governments to facilitate this transition through education and action. Scientists are improving their ability to demonstrate the link between climate change and weather events, and journalists, business leaders, and politicians are starting to take notice.

Global climate negotiations have often been viewed through the lens of the prisoner’s dilemma which suggests countries will act in their own self-interest. However, as the arbitration has continued to play out, the world is slowly realising that this isn’t a one-time game, it’s an iterative process, and that co-operation and collective action create the best possible outcome.