A Brief History of Climate Progress

In this post from NET-ZERO:

What were the key breakthroughs which built our understanding of climate change? Over 100 years of climate science and predictions.

What are the UNFCCC, IPCC, and the Kyoto Frameworks? Global agreements on climate action and what they mean.

How do the Paris Accord and NDCs work and are they enough? Agreements, commitments, and implied warming.

The Industrial Revolution

Thanks to the industrial revolution we are living through a period of unprecedented wealth, quality of life, and peace. However, another all-the-more subtle story has been playing out through the last 200 years. Since 1824, when Joseph Fourier first proposed the “greenhouse effect”, we have been unravelling the complex science of global warming and the unforeseen damage that burning fossil fuels is having on the planet. We are also coming to understand the damaging consequences of inaction, the risk of dangerous tipping points, and the possibility that humanity could be dragged back into destitution.

Understanding Our Impact on the Climate

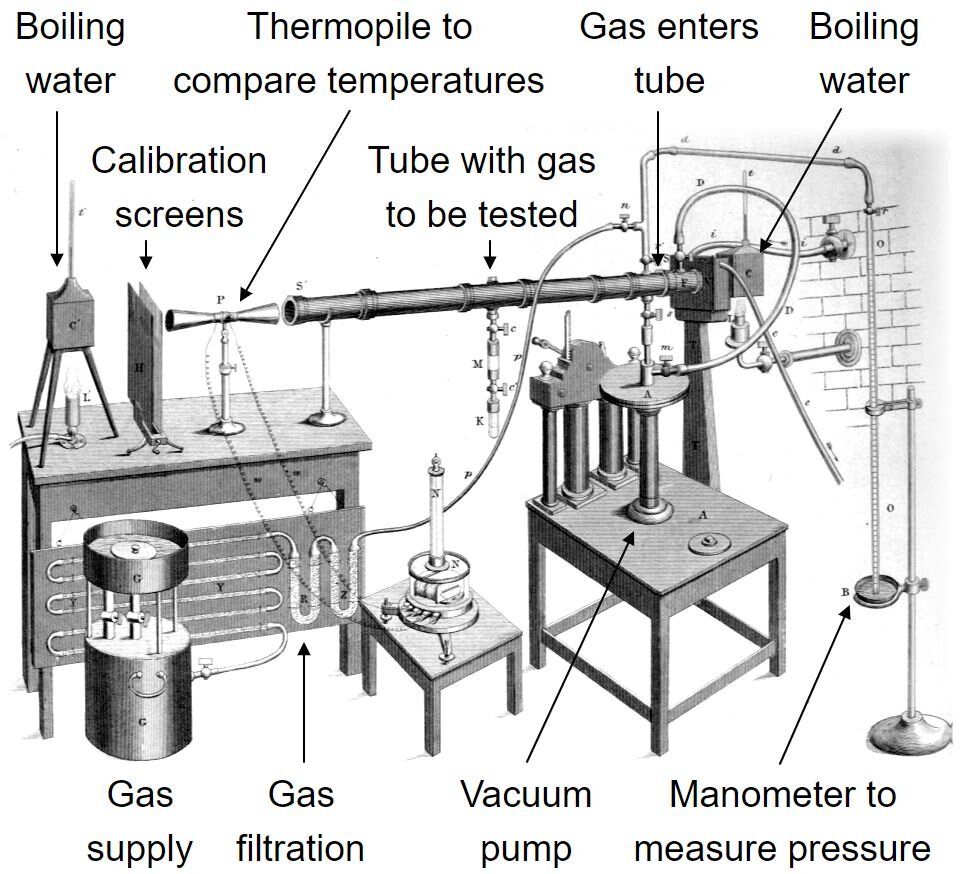

The story of global warming has many chapters and many prominent actors, from the pioneering scientific work by Foote, Tyndall, Arrhenius, and Callandar in the early twentieth century, to the definitive understanding and scientific basis for climate change pieced together by Revelle, Keeling, Manabe and Wetherald (amongst many others) in the fifties and sixties.

By the early 1970s, John Sawyer (correctly) predicted 0.6⁰C temperature increases in the twentieth century, the CIA secretly acknowledged global warming was already happening, and Wallace Broecker coined the term climate change.

In the 1980s, attention was temporarily diverted from the climate to the hole in the ozone and the Chernobyl disaster, until James Hansen delivered his famous speech to US congress in 1988 stating his team were “99% sure global warming is upon us”.

The IPCC and UNFCCC

The intergovernmental panel on climate change, the IPCC, was established in 1988, stating two years later, in its first report, that the planet was likely to warm by 0.3⁰C per decade under a business-as-usual scenario.

The IPCC is a United Nations body for assessing the science on climate change. The IPCC does not carry out original research but is rather a collection of around 200 experts nominated by governments all over the world which review and bring together the scientific literature. The IPCC release major Assessment Reports (AR) every 5-8 years which are considered the gold standard in climate change knowledge. The accompanying summary report for policy makers has summary statements which are negotiated and signed off by global governments.

In 1992, the Earth Summit in Rio saw the signing of the United Nations framework convention on climate change (UNFCCC), an international treaty based on the pillars of stabilising the climate at safe levels, whilst recognising differing responsibilities across the world, and later extended into the Kyoto protocol (1997) which agreed developed countries would cut emissions by about 5% relative to 1990 levels.

The third IPCC report, in 2001, projected temperatures in 2100 reaching 1.4-5.8⁰C warmer unless something was done. The fourth IPCC report, in 2007, started to flag the risk of dangerous climate tipping points.

By 2008, the world was realising we needed to move faster in order to effectively combat climate change and the fifteenth conference of parties (COP15) in Copenhagen, 2009, was the platform for change. However, the global Credit Crunch, in late 2008, had already diverted attention and, in the weeks leading up to the meeting, a network of climate deniers leaked partial extracts of hacked emails from a number of climate scientists at the University of East Anglia in the UK, misrepresenting the content, seeding doubt, and creating a media fuelled smear campaign to disrupt the talks.

Copenhagen resulted in no binding agreement and very little progress. It wasn’t until 2015 and COP21 in Paris when a binding global agreement to limit emissions was reached between over 190 countries. It may have taken nearly one quarter century of talks, but Paris represented a level of international cooperation not achieved since the nuclear non-proliferation treaty in 1968.

The Paris Accord

The long-term objective of the Paris Accord is to make sure global warming stays “well below” 2⁰C and to “pursue efforts” to limit the temperature rise to 1.5⁰C. Nationally determined contributions (NDCs) on agreed emissions limits by 2030 are submitted by each country and include roadmaps as to how the reductions will be made. Developed countries also committed to at least $100 billion of funding to developing countries each year to support the transition. National emissions stock takes are recorded every five years and reporting is a legal obligation but, unlike Kyoto, the emissions targets have no legal binding or penalty for non-compliance.

Paris represented a real political breakthrough in climate change action and yet since 2015 emissions have continued to increase and concerns have continued to grow louder.

Nationally Determined Contributions

Based on accepted or proposed NDCs, major developed economies are unconditionally committed to reducing emissions by 25-55% by 2030 (as of mid-2021). Developing economies are committed to either absolute reductions or relative limits - which allows some countries to increase emissions over the next decade.

More than half of developing countries have nationally determined contributions conditional upon receiving technology transfer, financing, and capacity building (skills) from developed countries which are still not being paid in full.

As commitments stand, global CO2e emissions will remain at roughly the same level (~50 billion tonnes per year) for the next ten years. In just one decade we will add another ~500 billion tonnes of CO2e to the atmosphere and blow through most of the remaining carbon budget to limit warming to 1.5⁰C (one third of the remaining 2⁰C budget).

Ratchetting up Ambitions

Despite 200 years of ground-breaking science, unprecedented technological progress, and a quarter century of international talks, global emissions have continued to rise. If we don’t accelerate action, the planet will be at least 3⁰C warmer by 2100.

Individual country emissions reductions targets (NDCs) must continue to ratchet tighter, these targets must be backed up with credible action plans and measurable milestones, and commitments by developed countries to developing countries must be met if we are to avoid potentially dangerous tipping point temperature increases and to create a just and favourable transition to zero carbon.