Limits to Growth?

In this post from the book net-zero:

A short history of doomsters and boomsters featuring Dr Strangelove, twenty billion chickens, and Playboy magazine. At the heart of this story is a wager over the future of our planet. A bet between a celebrity biologist and a subversive economist with diametrically opposed visions of the future.

This story strikes at the heart of the debate on climate change and asks:

Is climate change the ultimate limit to growth? Or

Can human innovation drive infinite prosperity?

By most measures the industrial revolution has been of great benefit for humanity; however, it has also changed the planet as never before. For the first time in the four billion years of life on Earth, a single species has begun to permanently reconfigure the natural landscape, repurpose the Earth’s natural resources, rewrite the rules of evolution, and reengineer the climate.

Oil-powered, mechanised agricultural machinery has turned one third of all dryland from forests into fields of regimented crops and animal pastures. Humans account for just 0.5% of animal biomass on the planet and yet we use 25% of the primary production of land based plants. Domesticated animal flesh used to feed humans now outnumbers large wild animals by seven to one - with half a billion pigs, one billion cows, and over twenty billion chickens on the planet at any one time.

Extraction of fossil fuels has been used to power mining and for purification and chemical transformation of natural minerals to build sprawling cities covering 2% of Earth’s land. Oil-powered travel across land, sea and air has brought once disparate geographies into a single ecosystem and redistributed once distinct species and diseases.

We humans began our training as subsistence farmers and two hundred years later we have graduated top of the class: the first species on Planet Earth to yield the power to transform Planet Earth itself.

The exponential rise in human population, consumption, and changes to the natural world have led many to question the limits to increasing prosperity and population growth. The original doomster Thomas Robert Malthus and his fear of exponential growth would inspire the works of many famous 19th century scholars, from British economist David Ricardo who warned of land scarcity and rising rent creating unsustainable inequality, to the German philosopher, Karl Marx, who feared the capitalist system would concentrate industrial production in the hands of the few, leading to limits on growth and even revolution.

“This law of capitalist society would sound absurd to savages, or even civilised colonists. It calls to mind the boundless reproduction of animals individually weak and constantly hunted down”. Karl Marx, Das Kapital, 1867

Roll forward a century or so and, following the post war boom, concerns over the rate of population increase resurfaced in the 1950’s and 1960’s, the Zeitgeist was captured by Stanford University Professor Paul R. Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb, published in 1968. The book predicted global famine in the coming decades. He and his wife argued that population had already doubled from two to four billion people in just one generation and, unless something was done, it was on track to do so again.

The Ehrlichs were convinced that limiting population was the only way to live sustainably on our allotted sources of natural income and without squandering Earth’s natural capital of non-renewable energy, minerals, and soils. Ehrlich asserted that food production was already near limits and the choice was stark: either “population control or the race to oblivion”.

As the Ehrlichs were worrying about population growth, many others at the time were preoccupied with concerns over peak oil and the limits to fossil fuel production. M. King Hubbert, a geophysicist working at Shell in the 1940s and 1950s, devised a mathematical model to link fossil fuel reserves, discovery rates, and output, in order to calculate peak production rates of finite resources. His models correctly predicted the peak of traditional US oil production in the 1970’s and he went on to estimate that global oil would peak by the year 2000.

In 1973 the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) declared an oil embargo on nations supporting Israel in the Arab-Israeli war. This coincided with global oil wells running at full capacity and plunged the western world into crisis. The price of oil quadrupled, gasoline was rationed, and the US imposed a 55mph driving speed limit in an attempt to curb consumption.

Worries moved from food shortages to energy shortages.

Concerns were further heightened after the publication of Limits to Growth in 1972. The report was researched and written by four scientists at MIT for The Club of Rome, an international collection of businessmen, scientists, and statesmen trying to better understand global problems as part of larger interconnected systems. The team of four scientists built an early computer model called World3 which linked changes in population, resource use, and pollution, using the ideas of economic investment and consumption. The scientists input the rate at which technologies improved to try and understand not only the limits to sources of energy, food, and minerals but also the ability of soil, water, and the atmosphere to accommodate pollution: limits to the Earth’s sinks. The idea of sources & sinks was a more nuanced take, employed to estimate the carrying capacity of the planet; the team estimated that the quality of life for humanity would rapidly deteriorate at some point over the next 100 years. They calculated that the only way to avoid disaster was through a combination of limiting further population expansion, ending consumption growth, and pushing sustainable technologies as hard as possible.

By the end of the 1970’s, limits to growth concerns had reached the highest levels and US President Jimmy Carter commissioned Global 2000 to better understand the problems.

The Global 2000 report surmised, barring a revolutionary advance in technology, life for most people on Earth would be more precarious in the year 2000 compared to 1980, unless the nations of the World acted decisively to alter ongoing trends.

The growing body of work by scientists and environmentalists was impressing an ever more dire vision of the future in the public consciousness. The possible response to these limits started to attract the attention of liberal economists who saw a rising threat to free markets and unhindered consumption.

Julian Simon, a professor at the University of Illinois, was one of those economists. He had gained an MBA in 1957 at the University of Chicago business school, around the time that Milton Friedman was challenging Keynesian ideas of big government in favour of deregulation, free markets, and printing money. These ideas no doubt influenced Simon and his early work focussed on the declining cost of food, and on demographic economics which led him to challenge the doomsters world view: asserting that a larger population is actually of benefit to everyone because more people equals more innovation.

He was convinced that although material supplies are physically limited on a finite Earth, they are economically infinite because technology creates more efficient use, enables resources to be recycled, and markets will ultimately find substitutes, where necessary. Should resources run into short supply, prices increase and attract more efficient use, new supply, or alternatives:

“We find new lodes, invent better production methods, and discover new substitutes”. Julian Simon, Science, 1980

In collaboration with Herman Khan, who had been a prominent US cold war strategist, a futurist and the inspiration for Stanley Kubrick’s title character in the film, Dr Strangelove, Simon published a book in 1984 called The Resourceful Earth, a direct attack on the ideas of the ‘Global 2000’ report.

Simon and Khan asserted that by the year 2000 the world would be more populated but less crowded, less polluted, more economically stable, and less vulnerable to resource supply disruption.

Yes, problems would arise, but capital markets and society would find solutions and leave the world a better place. The book was pro-nuclear in the long run, anti-big-government and, at its core, made the case for the capacities of market substitution to create plentiful resources.

Animosity between Simon and Ehrlich had been simmering since the publication of The Population Bomb. The book had become an international bestseller and Ehrlich’s celebrity status was consolidated with the publication of opinion pieces and his message of doom, everywhere from the Washington Post to Playboy magazine. In his regular appearances on The Tonight Show, he forcefully delivered his message of population control or impending doom to large audiences.

He dismissed Simon’s theories of infinite growth and referred to him as the “leader of a space age cargo cult”. Infuriated by the widespread attention being showered upon Ehrlich, and following Ehrlich’s claim that he would take even-money odds on England not existing by the year 2000, Simon decided to call him out.

Simon challenged Ehrlich to choose any natural resource he wanted and wagered that the price of those commodities would decline over any period of time greater than one year because technology would improve and substitution would occur. Ehrlich took him up on the offer and in 1980 the two academics agreed to bet $1,000 on whether the price of five metals would rise or fall over the next decade.

The rivalry between Ehrlich and Simon represented the growing division between scientists or environmentalists and liberal economists. The limits to growth thinkers reasoned that Earth’s resources were finite and therefore consumption or population must be regulated - they became known as the neo-Malthusians.

Those liberal economists who believed in the power of capital markets, substitution, and indefinite growth became known by the derogatory term ‘Cornucopians’, after the mythical horn of plenty from Greek mythology.

American economist Kenneth Boulding, giving evidence at the congressional hearing on the Club of Rome report, famously quipped

“Anyone who believes that exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a madman or an economist”. Kenneth Boulding, 1973

US journalist and author Max Lerner meanwhile evidently disagreed, writing in mockery:

“Ashes to ashes. And dust to dust. If the bomb doesn’t get you. Exponential curves must”. Max Lerner

So who is right? Are we heading for Dystopia or Utopia? Doom or Boom?

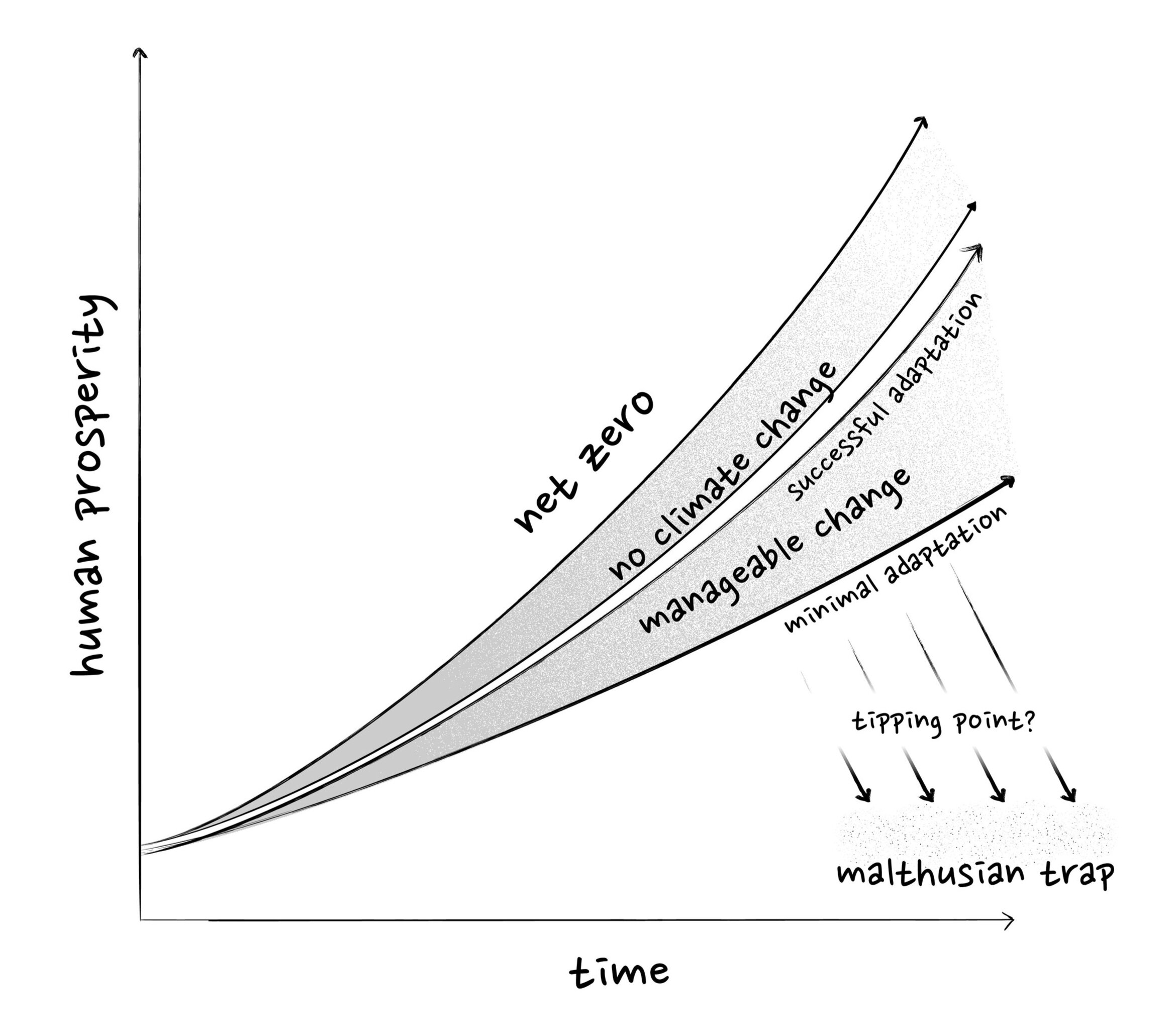

These are the ideas I explore in my draft book, net-zero, where I demonstrate how the same science, economics, and technology of climate change can be used to alter projections of the future by tweaking just three fundamental ‘dials of doom and boom’: the rate of physical change, the value ascribed to future generations, and the speed of technological learning.

And yet, already emerging, is an alternative ending. I argue, we are at a juncture where the dials of doom and boom are sufficiently narrow to assert that a rapid transition to net zero will create a win-win outcome for all sides of the argument.